"I never get tired of it"

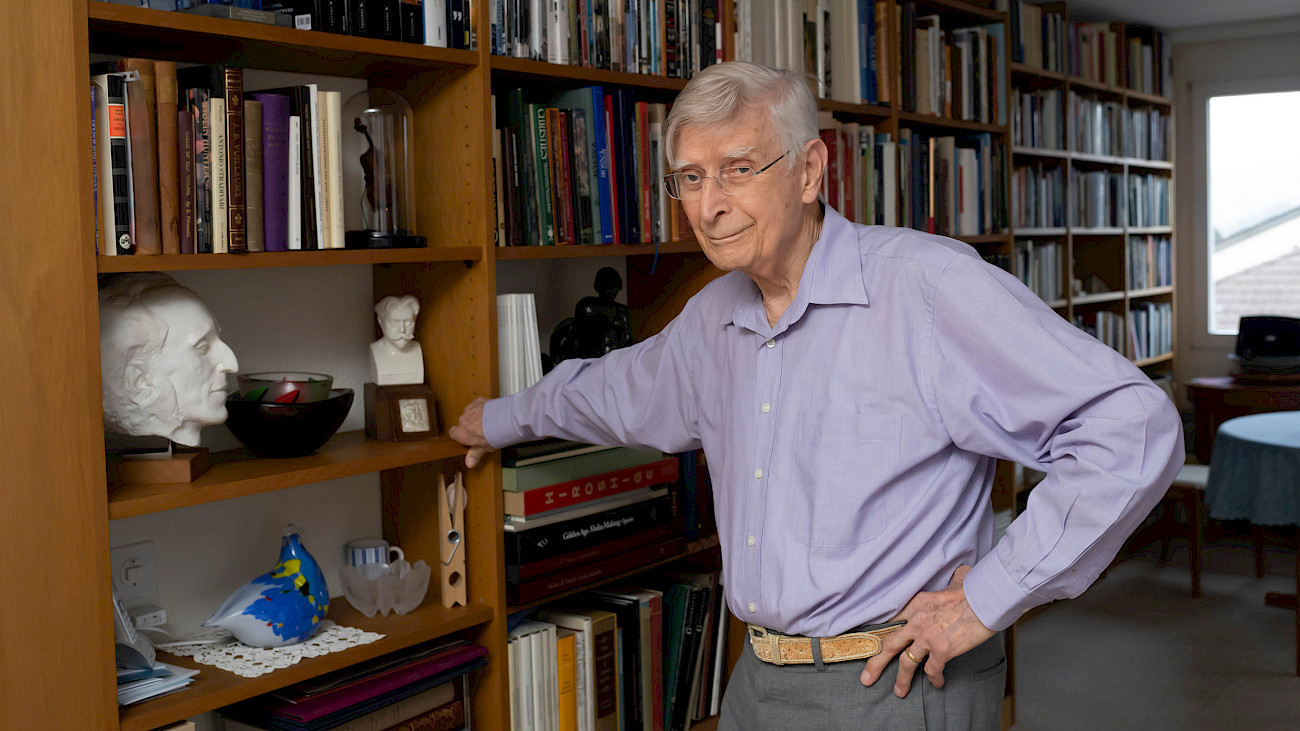

Maestro Herbert Blomstedt turns 97 in July - and is bursting with artistic energy. In an interview in his Lucerne flat in spring 2022, he spoke about defiant curiosity, his large private library and souvenirs from his fulfilling life as a conductor.

Mr Blomstedt, we had the pleasure of experiencing an impressive Bruckner Fifth with you in June 2021. You follow new musicological editions and start studying the scores of the works you conduct long before a performance. What else influences your view of these masterpieces?

The perspective is always changing. From day to day, actually, even if it's unconscious. You may only realise this later. Bruckner's students were also very enthusiastic and certainly only meant well by him when they heavily edited his works. I don't think Bruckner would have wanted it that way. He always built expression into his works, into the inner construction of the work. You don't need external means like ten extra trumpets. It's actually a sign of weakness if you can't create the right balance from within - but only from the outside. Maybe it impresses the audience for a short time or it appears in the newspapers and you think it's important, but it's not that important. It is much more important to study exactly how these works are made. When you pursue these ideas, you realise how your imagination works. New things always emerge from studying the old. And that is very impressive. That's why these works sound so complete. It's not a series of beautiful ideas. There is a lot of work between these beautiful ideas, which perhaps come once a year. That's the case with Bruckner, but also with Beethoven and Brahms. There are beautiful ideas, but that's not how the works were created. That's the work of a composer - and that's what makes the works unified and great, so rich and meaningful that you never get tired of studying them. You always discover new things.

That sounds like your idea of why you keep questioning your own interpretations?

As I understand it, it's about putting something up for debate, even a little bit of doubt. That's fine, but ...! The composer works less in this way. He discovers new things himself. He is never satisfied. Not that he says: No, that was wrong. That's not the point. It's not about new truths, but about new variations, new contexts. That's what makes the composer's life so interesting. And for the interpreter who has the time and the will to pursue this, it's incredibly exciting. I never get tired of it! I'm like a curious child. Do you have children? You know, at the age of three, four or five they ask questions all the time. They want to know everything. That's sometimes very tiring for parents - you're grateful for it, but sometimes you lose patience. But no, you always have to be curious. With every artist who has no problems and thinks everything is good, it is questionable whether he/she is an artist at all. If it comes too easily, then you become conceited. Then you stop looking and that's the end of it.

This curiosity is also evident in your programmes with the Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich, with which you have been associated for forty years. At your Zurich debut in March 1982, you conducted an all-Beethoven programme, followed shortly afterwards by a work by John Adams. In December 2022, you will conduct Franz Berwald's Symphony No. 2. Do you choose your programmes differently today than in the past?

Yes and no. When you are the head of an orchestra, you also have a special responsibility. You have to plan the repertoire so that the old is not always repeated. And when you choose new pieces, you have to make sure that it's not just about novelty, but also about quality. You are also a representative of local musical life. And the audience should also be able to develop. As a manager, you have many tasks. If, on the other hand, you only do one concert as a guest, you have completely different possibilities and fewer constraints. You can pursue your own wishes a little more. And sometimes I'm sorry that the audience doesn't yet know what I've discovered. You want to pass that on. So there's a bit of missionary in every musician.

What role does the audience play in your selection?

The audience is a little different in every city, and that's a good thing. Even as you get older, you can't just fall back on a few warhorses because you think you'll be more successful. That's primitive, actually abhorrent. This point of view of "Will I be successful with it?" has never occurred to me. I am convinced by a piece and the audience should then discover it. But I've never given in to the public's taste. Perhaps that has something to do with my upbringing. I was always suspicious of the popular. The catchiest, the easiest to digest, where you don't have to make an effort, is never the best.

What else was formative in the selection of your repertoire?

In Gothenburg, during my student years, there was a thriving musical life. The merchants financed it with their money. There was no symphony orchestra in Stockholm, but there was in Gothenburg. Here, independent of the royal family, people experimented and looked for the best. The relationship is similar to that between Dresden and Leipzig in Saxony. In Dresden, it was the king who made wonderful things possible early on. Leipzig followed suit 200 years later, then came the rich citizens: We don't have to adhere to royal taste, we do what we think. That creates a lot of interesting tensions. And I always look for the best. People might say I'm a snob. But I follow good advice, as Goethe said: look for the best mates! You only have to go with people who are better than you. That's wise advice!

On the occasion of your 85th birthday, you proclaimed the "Mission Stenhammar" to rediscover the works of Wilhelm Stenhammar. What is the current status of this mission?

Of course, there is a bit of defiance in this attitude. But defiance is good! It's especially good for artists. It shouldn't harm other people. But it is a great driving force to do something good. One example of this is Stenhammar, who worked in Gothenburg - also in Stockholm, where he was born. But he is buried in Gothenburg, which was the end of his career. He was a great champion for other composers. Not for himself! His contract stipulated that he was allowed to perform one work of his own every season. For the first five years, he didn't perform any of his own works at all. Yet he was a great composer. Instead, he worked for others, completely selflessly. Also for Carl Nielsen and for Jean Sibelius and all the other great composers around him.

How did Stenhammar stand up for these composers?

The most difficult Sibelius symphony for the public is No. 4. Everyone loves the first symphony. These are somewhat circus-like, very captivating, moving pieces, very pathetic, marvellous. But the Fourth is completely different. Solitary, isn't it? The audience didn't understand anything, and back then in Gothenburg most of them left after the first movement. They didn't boo or anything, but they said: "That's not for us, the others can hear it. And after the second set, some of them left again, and so on. In the end, there were only a handful of people left in the hall. But Stenhammar was convinced: "This is a masterpiece. He wasn't going to accept that - he was defiant too. And what did he do? Something marvellous! He wrote a very friendly article in the daily newspaper: "Dear friends, you don't realise what you've missed. But I'll give you a chance. Next week we'll change the programme and play this symphony again." That's how a friendly man of defiance does it, a fighter! His reaction is not: "Yes, then we won't play so much of this music so that people are always satisfied. No, no, they have to hear it. And what happened? Everyone in the audience stayed. He was successful with his defiance. That's how you can stand up for things you believe in.

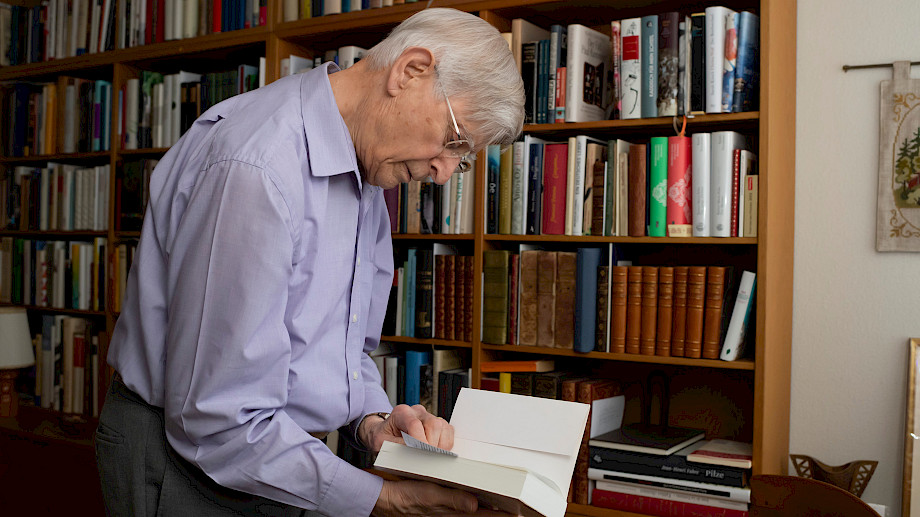

We were just talking about Gothenburg: That's where the majority of your library is located - 500 linear metres of scores, books and recordings. In the smaller part, we are right in the middle of it. What does your library mean to you?

It started with sheet music, of course, when you have so much curiosity for music. Before I made my debut as a conductor, I was a musicologist. There is a lot available in books. I also worked in so many countries, Sweden was just the beginning: I spent the next few years in Norway, the following ten years in Copenhagen, then 15 years in Dresden and then in America. You always feel the need to engage with these new cultures. I can't be a chief conductor in a country and not know the culture. When I have to make decisions, I have to balance this with what I know about these people, what feelings and what culture they have as a background, in order to do justice to what they need. So I also had to do a lot of reading. I particularly remember what it was like when I came to Copenhagen: I had little idea about Danish painting, philosophy, literature, but I had already heard of Søren Kierkegaard - the great philosopher. On the very first day, I bought all of his works - 22 volumes. That was of course very optimistic (laughs). But I found it very exciting. And of course the library grew very quickly as a result. Now I've been retired for 25 years and, because I don't have any administrative tasks, I have a bit more time to fulfil my thirst for knowledge. That never really stops.

What are you currently reading?

There are many, many wonderful books on the table, tomes. These are art books. Very recent: I had a visit a few hours ago from an antiquarian bookseller from Berlin, a very good friend. I had ordered two things from him that I was very interested in. One was the "Book of Hours" by Rainer Maria Rilke. I've actually had this book for a long time, but it's in its third edition. I even remember what I paid for it: 65 euros in a second-hand bookshop in Leipzig. Very nice, small format. Now to have the first edition of the book in my hand is wonderful. Marvellous. Wait, let me read you something from it: "I circle around God, around the ancient tower, and I circle for thousands of years; and I don't know yet: am I a falcon, a storm or a great song." The meaning is: the tower is a symbol of God, something solid. And falcons fly around the tower. They have built their nests in the tower. Security in God. He also seeks security in God. I circle around this tower, and it has been circling for thousands of years. That means not only he, but all artists seek God - overtly or covertly, even if they don't know it. Am I just a hawk? Or am I a storm? One accuses him, and one scolds God, and all sorts of things. Or a great song? There is only one last possibility: God is God and I am just a little man. A very beautiful poem, full of meaning in just a few lines.

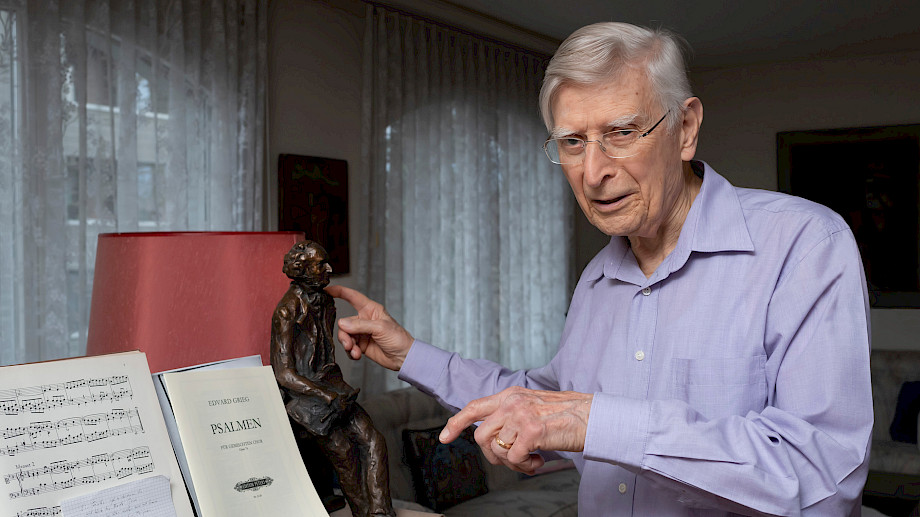

You were Gewandhauskapellmeister in Leipzig. What memories of previous stations such as Dresden, San Francisco and Stockholm surround you here in Lucerne?

I know a lot of artists from the orchestras. And some of them have given me small works of art that they made themselves. I have something very beautiful from a musician in Leipzig, Felix Ludwig: (Goes to his grand piano.) It's a small bronze statue of Mendelssohn. He's sitting there on my grand piano: on a stool, with the score in his hand and a baton. He looks a bit tired after a rehearsal. And I sometimes talk to him and get advice. There are only two of them. I've also bought a few things, like this bust of Arthur Nikisch - one of my predecessors as Gewandhauskapellmeister. (Points to a ceramic.) This is a ceramic from the wife of Ingvar Lidholm, the great Swedish composer, certainly the greatest composer in Sweden after Stenhammar. I conducted a memorial concert in Stockholm in January, with many of his works. I insisted that it had to be shown on television so that people wouldn't forget that he was a particularly great composer. A bit of defiance too (laughs).

This painting was made by an artist from San Francisco. (Points to a large-format watercolour.) His name is Gary Bukovnik, a great music lover. Every year he made a poster with flowers for the San Francisco Symphony, he only paints flowers, watercolours. After my ten years as conductor in San Francisco, he painted this picture for me: These are ten bouquets of flowers. The Staatskapelle Dresden gave me this painting when I became chief: It's a biblical story by Hans Jüchser. This is King Solomon, who was famous for his wisdom. Two mothers came to him, and one said, "This is my child. The other said: No, this is my child.

The judgement of Solomon.

Yes, yes, that's it. And the orchestra gave me this picture when I became boss. They hoped that I would also be able to make Solomonic judgements. Because there's a lot of need for it (laughs).

How has your day-to-day work changed over the decades?

Not very much. Everyday life has always been very busy and still is. I've just returned from the USA and am travelling on to Sweden. A normal day is: I have rehearsal at ten o'clock. Before that, I have breakfast and take care of business. I want to be there half an hour before rehearsal, and then it's rehearsal. Maybe one or two rehearsals until about four o'clock in the afternoon. And then I go home again. I'm on my own, I cook for myself. That's also variety, it's fun. I eat so much in restaurants. When I'm here, I want to spend as much time at home as possible.