«It is Also a Question of Chemistry»

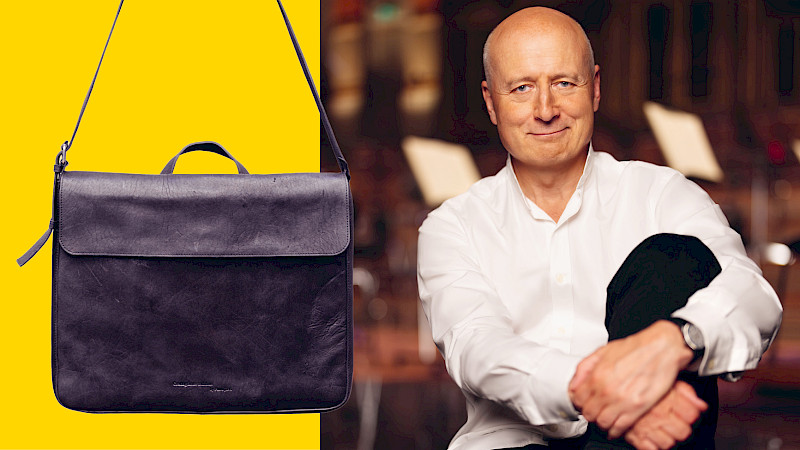

Jean-Christoph Hannig is part of the team that tunes and looks after the grand pianos in the Tonhalle Zürich. He not only knows the instruments, but also how the pianists tick.

You have just tuned a grand piano – and you finished faster than planned. Why?

You never know how long you'll need. It depends on many factors: If the instrument hasn't been played for a while, if there have been climatic changes, if it was set up by someone else the last time ...

Do you notice which of your colleagues played the last time?

Fortunately, hardly at all. We look after the pianos in the Tonhalle Zürich in a team of four from Musik Hug, and we work so well together that I usually can't tell who tuned the piano last. Only when one of us looks after an instrument exclusively for a long time do you notice the signature.

How do you show your own style?

I have to elaborate a bit: In the 19th century, the strings in grand pianos often broke, they were too soft for the tension they were exposed to. A Franz Liszt wore out three pianos in one evening. So tougher wires were developed; today piano strings are the hardest industrially produced wires ever – if you buy a pair of pliers in the DIY store, it says how thick the piano wire is that it can cut. But this hardness has a tonal effect: It causes the overtone series to be slightly spread. We know this effect from bells, where the overtone series is sometimes spread so far that our ear no longer perceives the sound as a single tone. With the piano it is much less extreme, but still noticeable. This means that when tuning, I also have to spread the intervals slightly so that the sound is round. How far to go is one of the decisions we have to make when setting up the instrument.

Are there pianists who make special requests in this regard?

Rarely. But there are some who have their own experts. Maurizio Pollini, for example, has been using the same tuner for decades; András Schiff or Hélène Grimaud always work with the same specialists. Setting up an instrument is not least a question of chemistry: even with us it happens that things don't go so well with someone; then the next time someone else will look after that pianist.

How close is the contact?

As a rule, we don't have much to do with each other. We tune before every rehearsal and every concert, but usually we only meet the pianists at the dress rehearsal. Then it happens that we look at something together on the instrument – this note is a bit too loud, that one too sharp. But requests in advance are rare. An interesting exception was Víkingur Ólafsson last season. He really wanted to ensure certain functions, in the repetition, in the release - and he requested it exactly like that, in our technical language.

That is unusual?

Yes. There are musicians who really deal with piano construction. Krystian Zimerman is probably the most extreme example; he works on his instruments himself and also tunes them. Till Fellner or Grigory Sokolov also know exactly how a piano works. But most of them know little more than the key-note connection, and that is sometimes a problem. Because that way they can't name what exactly they want either. If, on the other hand, a Sokolov says what he imagines: Then it's a challenge, it's also fun.

The first wish is probably for a particular grand piano. How big is the selection in the Tonhalle Zürich?

We have two instruments in the large Tonhalle and another in the small one. They can't be exchanged at will because the transport is expensive. That's actually a pity, because the grand piano from the small hall would be a wonderful addition.

How would you characterise the two instruments in the large hall?

In terms of type, they are both the same: Steinway grand piano, model D, 274 cm long. They were also built at almost the same time, about 13 years ago; the serial number indicates that they were built no more than two months apart. But they are set up differently, i.e. the hammer heads were worked on quite differently. One grand piano is percussive, brilliant; you need it for works with large instrumentation, for those that demand a lot of power and sound. The other is more classical, a little more delicate, also easier to control.

In what way is the brilliant grand harder to control?

It quickly becomes so loud that it is difficult to shape the timbres precisely. Whereby there are always surprises. Rudolf Buchbinder, for example, played his «Diabelli Project» on this piano – and it was very delicate at times. Or Víkingur Ólafsson again: he absolutely needed this piano for the John Adams concert. He said that it was almost aggressive, and that he had a problem with it for Mozart. But then he played a movement from a Bach organ sonata as an encore: he showed how he can control this piano, what colours and registers he is able to conjure up. You could really hear great mastery there.

How much do the differences have to do with the set-up, how much with the pianos themselves?

The furnishings are decisive, but there are also differences in the instruments. For example, the spruce woods for the soundboard are selected very rigorously. Nevertheless, there are variances of up to 300 percent in the technical characteristics. And that's just the soundboards – we don't even want to talk about the felt on the hammer heads, about all the manual work that goes into it.

But it is true that the differences in sound are much smaller than in the past?

Yes, and I personally regret that somewhat. This is not only true for Steinways, all other manufacturers have also come closer to this sound ideal. When András Schiff brings his Bösendorfer to the Tonhalle Zürich, you can still hear a difference in the front rows. But in the back half of the hall, it is no longer perceptible. Personally, I would like to see a rethink here. You can hear in old recordings how much a work changes when it is played on a different instrument.

Despite the small differences, many test several instruments of the same model before deciding on one. Is it worth it?

Yes. When we buy instruments for Musik Hug, we always go to the Steinway factory in Hamburg. Just recently I was there again. They were very excited about my choice. As a technician, I naturally listen to different things than a musician. For me, the most important thing is that an instrument is even. And then I'm interested in how well I can influence it. Technically, it's easier to take a brilliant instrument back than vice versa.

Why?

The felt on the hammer heads is pulled around the wooden cores under high pressure and tension and pressed and glued. At the beginning this construction is hard, you have to soften it to make it sound at all. But when I start to cut into it to soften it, I always lose some of the elasticity. And I can never get that back.

Does an instrument change over the years?

Yes. If you take good care of it, it can actually last forever, the quality remains. But the timbre changes. An older soundboard develops a warmth in the tone that a young one doesn't have. On the other hand, some claim that an older instrument can no longer develop the same dynamics as a young one. By the way, there are pianists who specifically want young instruments, for example Grigory Sokolov. When he performs at the Tonhalle Zürich, we always lend him an instrument.

How do you look after an instrument properly, or rather: what are the greatest stresses and strains?

The worst are climatic changes, especially changes between humid and dry air. That's why frequent transport is also a stress for the instruments - when pianists like Pollini or Schiff travel around with their own pianos, it's a strain. Even if you tune them differently very often, that doesn't do the instruments any good. And when we talk about playing, the most extreme situation is that in a conservatoire: the pianos that are released for practising are in use almost around the clock. The hammer heads have to be replaced after six or seven years.

What is the case in the private sphere?

Here, too, climatic changes are the biggest problem. Underfloor heating is also unfavourable, because the heat rises into the instrument from below, directly to the climatically sensitive soundboard. Otherwise, you have to make sure that you have enough space, not only for the instrument, but also for the sound. We often see customers fulfilling a dream and buying a Steinway grand or upright piano. At the first service a few weeks later, they say: Everything is wonderful, but could you make it a little quieter?

And can you?

A little bit can be achieved through the furnishings. Sometimes we also attach foam between the beams at the bottom of the piano or at the back of the piano. But of course that also changes the sound. So I don't understand why there are no piano builders who specialise in this niche: There would certainly be a lot of interest in quieter pianos. By the way, even among professional pianists: Konstantin Scherbakow, for example, sold his grand piano because of the volume. He now plays an electric piano at home.

Translated with DeepL.com