"You feel safe in this sound"

Concerts can be emotionally moving, making music is good for you. No wonder, music therapy has a profound effect on both mental and physical ailments. And even for the very young.

The breakthrough came in 2020, at the University Hospital Zurich: for the first time, the effect of music therapy on premature babies was proven using imaging techniques. According to the study, the brains of the premature babies treated showed "significantly fewer delays in the functional processes between the thalamus and cerebral cortex, stronger functional networks and improved interaction between different brain regions, including in the areas relevant for motor skills and speech".

Selina Kehl, who talks about her work as a music therapist a few hundred metres away from the USZ at the University Children's Hospital Zurich, is delighted with these research findings: "It's good that such results can be scientifically proven." They don't come as a surprise to her: "I see what music can do in practice every day."

Since 2018, she has been working with children who have to stay in the children's hospital for months. Many of them are newborns who were born with a heart defect, a diaphragmatic hernia or intestinal problems. They have a stressful start to life, especially when they are in intensive care: Their beds are in open bunks, monitors beep all around them, they hear footsteps, voices, the clatter of doors. And time and again they have to endure examinations and procedures that nobody can explain to them.

A sounding cocoon

Selina Kehl feels this stress when she sits down at a bedside, she sees it on the screens. Perhaps she then starts humming and picks up the rhythm of the child's breathing. Sometimes she starts from a song, sometimes she improvises freely. She may then get stuck on a descending melody because she notices that the child relaxes and that the beats on the monitor become calmer. Or she sings upwards when she sees a newborn opening their hands. "It's often minimal reactions that show me what a child needs," she says. "It's about reading these reactions."

She visits the individual children two or three times a week, "continuity is crucial". In this way, the little ones get to know their voice, humming and singing becomes something familiar in an environment where so much is unpredictable for them: "It's really impressive how they calm down as soon as they hear the familiar sounds."

That's why it's also important to her to involve the parents as often as possible, "the children already knew their voices before they were born". In such family sessions, she often has a monochord with her, an instrument with many strings that are only tuned to two notes; it is a particularly robust custom-made instrument, "a normal wooden instrument would quickly break because we have to constantly disinfect it". When she places the instrument on your knees and strokes the strings, you can feel the vibrations and, thanks to the many overtones, a real sound space is created.

For Selina Kehl, this sound is like a cocoon, "you feel safe and connected in it". The hospital noises stay outside. And it is also easier for parents who don't usually sing to hum along or perhaps even sing their own songs: "Especially when they can't hold the child in their arms, this is a way to connect with them."

Sometimes she rewrites a song together with the parents. It then tells of the wishes and hopes for the child, of the worries they have, or simply of what is happening. And even if the children don't understand the words: "They realise exactly when they are being spoken to," says Selina Kehl. "The music isn't just there to calm them down: it also gives them impulses, creates closeness and arouses interest."

From the piano to the children's hospital

It's all about that, not about art - Selina Kehl experiences that elsewhere. She studied piano and teaches at the Männedorf Music School alongside her work at the children's hospital: "Music is a part of me, I enjoy teaching and it's important to me to continue practising and making music myself." Concerts are also about coming into contact with an audience; "in music therapy, this contact is simply much closer and more personal". That suits her.

Initially, she says, it wasn't easy at the children's hospital, "as a non-medical person, I first had to find my way around the intensive care unit and the team". She has now settled in and her work is appreciated, and not just by the doctors: "Until now, music therapy has been financed by foundations and donations, but this year the children's hospital has given a deficit guarantee for the first time; I was really pleased about that." It shows how important the music therapy programme, which was introduced seven years ago, is considered to be. "It's now clear that it's not enough to heal the body," says Selina Kehl, "the soul has to come along too."

Music therapy: three years of training at the ZHdK

Selina Kehl and Christian Kloter completed their training at the Zurich University of the Arts; both have a Master's degree in Clinical Music Therapy and - building on their first degree in music and social pedagogy respectively – have spent 3,000 hours studying musical, psychological, psychopathological, curative education, medical and art therapy topics. Music therapy self-awareness, internships and supervision are also part of the programme. In addition to this course, there are four other training courses in Switzerland on a private basis; graduates of these courses can also obtain a degree recognised under higher education law by upgrading to the ZHdK.

This realisation is not new. Even in ancient times, people knew about the beneficial effects of music. Medicine men from different cultures used sounds to put people into a trance. In Salento in southern Italy, the pizzica, to which people tried to dance tarantula poison out of their bodies, became a musical form in its own right. And all over the world, children are lulled to sleep with lullabies.

However, music therapy as such is still a comparatively young discipline that has developed in all possible directions since the middle of the last century. Very different approaches are taught, researched and applied. They can be roughly divided into receptive and active therapies. Selina Kehl often works with receptive methods in the paediatric hospital because the children are too small to make anything sound themselves. However, she emphasises that even the very youngest children are always active counterparts: "They make contact, interact and thus indirectly help shape the music." And as soon as they can handle simple instruments, they are happy to do so - they set a wind chime in motion, play with rattles, explore the monochord.

Whispering, tapping, droning

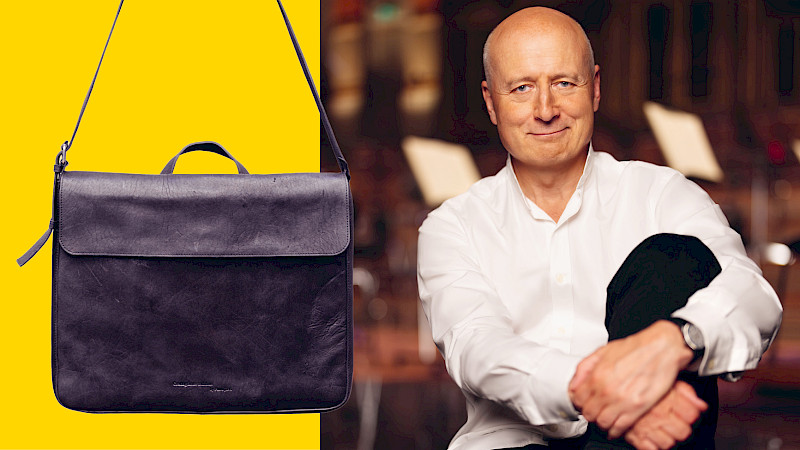

At Christian Kloter, active music therapy takes up more space, also in the literal sense. His studio in Rieden near Baden is full of instruments: There is a cello and a grand piano, various xylophones and drums, gongs and didgeridoos, a bowl of corn kernels and stringed instruments that you don't even recognise by name, in short: everything you need to make yourself heard whispering, crackling, tapping, booming or even melodically. You want to play with all of this right away, and that's exactly what Kloter's therapy sessions are all about: playing, the freedom to create sounds in whatever way suits you.

However, the game is serious. Those who come here need help; they are people "who have lost access to themselves or are trapped in agonising circles of thought," says Christian Kloter. They suffer from depression, anxiety disorders and post-traumatic stress disorder. "Music can lead them to their emotions, out of their thoughts. It can make something tangible that may have been hidden for a long time, and it illuminates things that would not be accessible to the intellect alone."

He also cares for dementia patients, who sometimes remember nursery rhymes even when they have forgotten almost everything else. And he lists the cases in which music therapy can also help: with eating disorders, for example, neurological diseases such as Parkinson's or multiple sclerosis, after strokes, with autism spectrum disorders, tinnitus and in pain therapy. It is also used in palliative care, where it is usually used receptively: "Sound can help you let go."

"Not just a gypsy trip"

So is music a panacea? No, says Christian Kloter, but like Selina Kehl, he is pleased with the research: "The effect has now been scientifically proven in many areas. Music therapy is nothing esoteric, it's not some kind of gypsy trip." Playing around with the instruments activates very different areas - physical, cognitive, social and sometimes even spiritual. You are in motion, feel the vibrations of an instrument or how your fingers glide over the strings. At the same time, you can hear the sounds you produce, change them, shape them, develop them further, pursue what feels right. In group therapy, you also notice what others are doing, how you are interacting with them - or not.

What happens is more fluid and open than what can be expressed in words: "Things are closer together in music than in language." Christian Kloter explains what this means with an example: "For example, someone can start by beating a drum with enormous anger. But suddenly the anger transforms into powerful, positive energy. This may then result in a certain calm, and suddenly sadness comes into play. If the patient allows it, a lot can be experienced directly through music."

The whole thing doesn't have to sound nice, "my motto is: don't try too hard". Nevertheless, expectations and experiences sometimes get in the way - unlike with babies: "Many people naturally know what a cello can or should sound like. I then suggest that they try an instrument that they don't know yet and can therefore explore more impartially."

Keyword "uninhibited": How do you trick inhibitions? How do you get people out of performance patterns, how do you get them to sing and play when they haven't done so for decades? Sometimes it helps to imagine a fantasy place, says Christian Kloter, "we then explore this place together, which has nothing to do with our world and can therefore sound completely different". Or he also addresses shame directly. "I then say: you see, I'm just as much of a clown here as you are, and it's fun - why should we stop ourselves?"

Test lying on the monochord

That sounds simple. The visitor realises that it isn't when she does a little test on the sound lounger in Christian Kloter's studio. It is a kind of oversized monochord with strings running underneath the surface. If you lie down on it, you can feel the vibrations, become enveloped by the sound, let yourself be drawn in, feel safe - until you realise that the instrument is tuned in fifths and the overtone spectrum is constantly changing: This reactivates the mind, the sound space breaks open and the effect fades. Engaging in therapy is also a matter of practice.

But you can start small, with the realisation that there is a little therapeutic power in all music. Going to a concert can stir you up, singing in a choir can improve your mood and make you feel better. Selina Kehl perhaps also finds improvising in hospital easy because she is used to performing. And for Christian Kloter, his youth spent in practice cellars is just as important as his initial training in social pedagogy. Sometimes, he says, he invites his former band mates to his studio in Rieden for a jam session. This has nothing whatsoever to do with therapy: "But it's extremely good."

Connect: Dancing with neurological challenges

The Tonhalle Society Zurich and Zurich Opera House, together with the independent performance group The Field and the Dance & Creative Wellness Foundation, are launching a new collaboration that is unique in Switzerland. The project is called Connect; it is a dance project for people with neurological challenges such as multiple sclerosis or Parkinson's disease. Dancing is an activity that has a positive effect on physical and mental well-being and quality of life, especially in the case of neurological diseases. Creativity, lightness, balance, expression, posture: all of these can be rediscovered through dance. The weekly dance training sessions take place at the Tonhalle Zurich and are led by professional dancers with the relevant expertise. In addition, musicians from the Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich will participate artistically in some of the sessions. The pilot phase of the project will start in February 2024; these first sessions are already fully booked.

Translated with DeepL.com