Fates are decided here

They are secret, controversial and highly complex: the auditions in which new orchestra members are selected. Or, in this case, new horn players.

Tuesday, 9 a.m., sometime in early summer. It sounds like horn and adrenaline in the Grosse Tonhalle. Spread across the stalls, 18 horn players sit and stand and play as if they were alone. They are all hoping to be on the Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich's list of newcomers a few hours later. In other words, they are among those who are called when a permanent horn player cancels - or when more horn players are needed for a Mahler symphony than there are in the regular line-up.

"Good morning," says the organisers of this audition at the front of the hall, welcoming the candidates. Anjali Susanne Fischer, who is responsible for the HR Orchestra and has organised the whole thing, explains the procedure. The orchestral horn players are also there, working together with a musician from the orchestra board as the audition committee. There are also two orchestra technicians, who have a few thousand steps and perhaps a few psychological challenges ahead of them: They accompany the candidates from the main hall to the audition rooms and from there to the club hall, where the auditions take place.

The term "audition" is actually far too objective for what takes place here. Auditions are the most secretive, controversial and complex events in the whole orchestra business. This is where existential decisions are made, where the future of the orchestra is decided.

The pressure is correspondingly high - for the candidates, for whom everything is at stake: career prospects, financial security, even a place to live. Once you have a permanent orchestral position, you often keep it until you retire. Later changes do occur, but they are rare.

Auditions are not easy for those who judge them either: after all, they remember exactly what it feels like; after all, they have experienced it themselves, once, twice, many times. And they know what their judgement means: "We take the whole thing really seriously; it's not easy when you can change someone's life or not," says violinist Isabel Neligan. There is also the responsibility for the orchestra: "Every choice has consequences and changes the human and musical balance. And if you only choose three or four new players with a similar orientation, this can have a long-term impact on the development of the entire orchestra."

The numbers

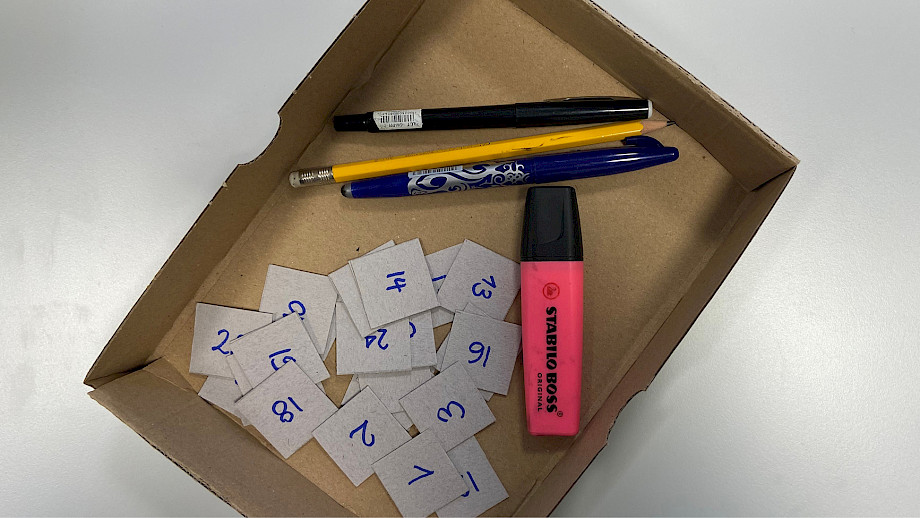

Back to the horn candidates. For them, it's not yet about a job for life, but it's about a lot: an entry into the orchestral world, a first step that can be followed by others in the best-case scenario. In the meantime, they have drawn lots, names have become numbers; auditions are strictly anonymous. Numbers 1 to 3 are then taken to the audition rooms. In the minutes that follow, you hear scales from one of them, the same tricky passage from the requested piece, Strauss' "Till Eulenspiegel's Merry Pranks", over and over again from the second. And from the third - nothing.

It's always like that, says orchestra technician Martin Kozel, "everyone deals with the stressful situation differently". For him and his colleague, the long-distance course has now begun. They will bring No. 1 into the club hall for the audition and at the same time take No. 4 from the main concert hall into the first rehearsal room. If possible, in such a way that neither the candidates nor the commission have to wait: Any unevenness in the process increases the pressure; you can feel this when you sit in front of the door of the club hall.

The candidates step out of the lift as if hypnotised (climbing the stairs is not recommended, otherwise you'll be out of breath before the performance); most of them only nod when Anjali Susanne Fischer checks once again that the right number has been brought in. Even in the hall, very few people respond to the greeting, according to the committee. If you ask the orchestra whether there is any truth to the rumour that many people take beta blockers before an audition, you get vague answers: Nobody has any personal experience, nobody thinks it's good or sensible. But everyone can imagine that it does happen.

Is this pressure necessary? This has long been the subject of heated debate in the orchestral world. Some say no: What is demanded at auditions has absolutely nothing to do with everyday orchestral life. After all, a perfect solo does not reveal whether someone can fit into an overall sound and whether they fit into the ensemble as a person. Or, in the case of solo positions, whether the person has the leadership qualities that are needed in such a position.

Yes, the others reply: Both the wind players and the section leaders in the string sections often have to deliver exposed solos in concerts; this is quite comparable to the stress of auditions. Everyone agrees that the situation is somewhat different for tutti parts. But how could a more realistic selection process be organised here? So far, no brilliant ideas have emerged anywhere.

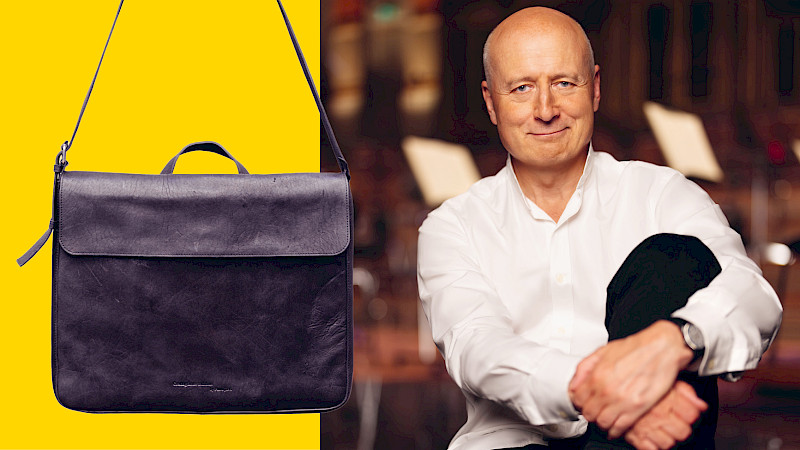

One thing is certain: sometimes the wrong decisions are made. That's why, after a successful audition, there is a trial year to test whether the newcomer really fits into the orchestra. Paavo Järvi says that the orchestra sometimes rejects someone after this year who it would have absolutely wanted after the audition: "That's normal." Conversely, there is no correction. Anyone who doesn't pass the audition stays out, even if he or she might have been the perfect choice.

The curtain

The first horn auditions are now over. The current candidate plays flawlessly, perhaps a little restrained - as far as one can judge from the door. Apart from the orchestra commission, no one is allowed into the hall, even the director Ilona Schmiel once asked in vain for an exception. Depending on the importance of the position, this orchestra jury is larger or smaller: if it's a solo position, fifty people sometimes sit on it. This is probably the biggest difference to assessments in other disciplines, says solo cellist Rafael Rosenfeld: "It's not easy to expose yourself to such a large group."

The group of potential new horn players is small, and something else is different than usual: for once, there is no curtain in the hall. This curtain normally ensures that the start of the first round is actually completely anonymous. Whether a woman or a man is playing, whether you know the person or not, whether a tutti colleague is applying for the part leader position or a young talent from South Korea - you can't see it, and it can't be guessed either.

For solo cellist Paul Handschke, this was quite pleasant. He successfully completed three auditions with the Tonhalle- Orchester Zürich: First as a trainee, then as a tutti cellist and finally for the solo position. "I was particularly happy about the curtain call at the last audition. Sitting in this cramped club hall right in front of all your colleagues, with Paavo in the front row - that's really tough." Paavo Järvi, for his part, is happy when the curtain disappears in the second round: "Making music is a physical affair, it's not just about sound, but also about presence on stage."

However, you get a little bit of this presence even without the visuals: This becomes apparent when listening outside the door. The 18 horn players have now completed their first round, and the differences are striking. You could hear bold and restrained interpretations; and while some immediately entered into a dialogue with the pianist Hendrik Heilmann, others seemed to play entirely to themselves in the hope that he would then adapt.

The pianist

The hope is justified, Hendrik Heilmann is an extremely flexible pianist and he is aware of his responsibility: "I always prepare very well for auditions and practise a lot, even if I already know the repertoire - so that my attention is fully focussed on the candidates." They all play differently and are excited in different ways: "You can tell when they come in what state they're in."

He sets the tone so that they can tune in and then they start. There are no arrangements or rehearsals beforehand, "there would be no point, I wouldn't be able to memorise the nuances of thirty interpretations". So it really depends on the moment - and for Hendrik Heilmann, it also depends on his stamina. The fact that he still plays just as well with candidate 28 as he did with candidate 1, "that's a challenge, not only musically, but also athletically".

The criteria

Break. The young horn players wait for the results in the large concert hall while the committee deliberates. The discussions are brief this time, and Anjali Susanne Fischer from the orchestra office soon emerges from the concert hall, looking somewhat thoughtful: only two of the 18 candidates will be invited to the second round, "I hope that we end up with at least someone". This is not a matter of course; important positions in particular often have to be advertised several times. It took three auditions before a new tuba player was hired; even a new solo clarinet player was only found after several attempts.

The criteria are strict, and rightly so. At the same time, they are almost impossible to define: "As soon as a certain level is reached, the judgements are extremely subjective," says Rafael Rosenfeld. All the orchestra members interviewed agree on only one thing: it's not about counting mistakes. "If someone has colours, a beautiful line and something to express - then I'm always in favour of progressing to the next round, even if something goes wrong," says Isabel Neligan. Paul Handschke once benefited from this: "I know for a fact that I didn't hit all the right notes in my solo audition, but I obviously still managed to convince the jury." He himself also looks at whether someone is having fun playing: "You can tell exactly whether someone is thinking that the first F sharp shouldn't be too low - or is actually making music." Rafael Rosenfeld agrees: "Those who play it safe might make it to the second round. But then they'll say, yes, that was good, but we're not really interested."

But what is good and interesting, who fits into the ensemble, who do you want to play with? Sometimes everyone agrees; for Paavo Järvi, this is "the best option, then you can be sure that you have chosen the right person". More often, however, opinions differ widely; then there are discussions, "sometimes it even comes to blows," says Rafael Rosenfeld: "It's often a painful process, many people become extremely passionate - after all, there's a lot at stake."

In the end, it takes a 2/3 majority in the vocal section, a 2/3 majority in the orchestra - and the approval of Paavo Järvi. He has the right of veto and can prevent a cancellation even if the whole orchestra is in agreement. He doesn't like to invoke this right, he says, "but sometimes it's necessary". He wants people who "rock the boat"; if he has the impression that a decision is too focussed on pleasant interaction, he opposes it. However, there are limits to his power: without the majority of the orchestra, he can't push anyone through. The orchestra is happy about this, because a chief conductor is gone at some point, but the elected person remains.

The feedback

And the candidates? What do they get out of all this? The rules are clear: what is discussed in the committee remains in the room; the fact that something sometimes leaks out is human, but not ideal. If someone knows who was for or against them, it's problematic for everyone.

But there is certainly direct feedback. "As a rule, after the first round, the people from the voting group go and talk to those who want to," says Paul Handschke. Sometimes requests also come in later, for example via Facebook. However, he is careful in his wording: "If I say to someone that your Haydn is simply not energetic enough, they might go to the next audition and go full throttle." Rafael Rosenfeld also knows what this means as a teacher: "You always have to follow up auditions like this with students. I encourage them to get feedback - but you have to categorise and put it into perspective."

And then it's about licking the wounds: Some musicians get over the hurdle the first time, others spend years travelling from one audition to the next; the price is high, both psychologically and financially.

The decision

In the meantime, the break is over and the two remaining horn players are brought into the club hall one after the other for the second round, now it's time for Strauss' "Heldenleben" - one of the most difficult horn parts of all. The discussion is short this time too: neither of them makes it onto the list of newcomers. If a horn is missing, musicians are "borrowed" from other orchestras until the next audition takes place. Anjali Susanne Fischer now only has one item left on her to-do list: "Shred biographies and sheet music with notes." So that the secret really stays secret.

—

Note

Every year, the Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich organises sometimes a dozen, sometimes considerably more auditions. Up to 320 applications are submitted each year. The number of candidates who are then invited varies greatly. In order to avoid drawing conclusions about individuals, we are not showing any photos of the horn audition described here - instead, we are showing photos of one for string trainees in which the curtain was also used. The successful candidates will play in our concerts this year.